A Conservation Bridge between Two Havens:

The A2A Corridor

By Spencer Busler, Assistant Director

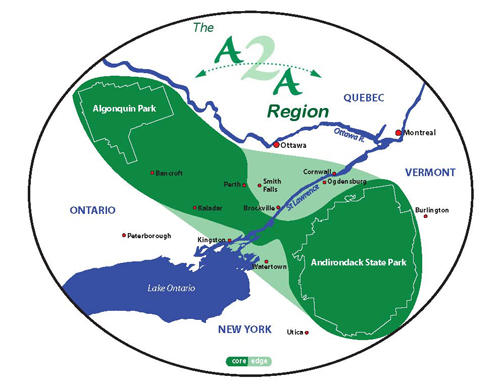

Not far below the flowing waters and rocky soils of the St. Lawrence River Valley lies an ancient hourglass. Within this hourglass flows not the sands of time, but the quiet and consistent movement of wildlife, people, and their genetic diversities. Stretching northwest from the peaks of the Adirondack Park in New York to the rugged boreal terrain of the Algonquin Provincial Park in Ontario, a granite ridge protrudes from the earth in the general shape of an hourglass. This expansive, densely vegetated ridge is known as the Frontenac Axis (or Frontenac Arch), and can be somewhat challenging to conceptualize while at ground level.

However, the Arch’s deep green forest blocks can be easily observed from far above the earth’s surface with the aid of satellite imagery. In fact, the bird’s eye view may be the very best way to visualize this resource, which has stayed relatively obscure to the many folks who work, live and play in the Thousand Islands and St. Lawrence River Valley region.

Once covered by a sheet of ice over one mile thick, the St. Lawrence River Valley’s underlying bedrock was resistant to the erosion of the glacial retreat about 13,000 years ago. Today the region is defined by rolling forests, meandering streams, vibrant wetlands and stunning outcrops.

We owe a great deal of appreciation for the landforms and ecosystems left behind to these receding glaciers. Their presence not only serves as one of the most important wildlife migration corridors on the continent, but they create two of the most fantastic natural settings that we know of: Lake Ontario and the Thousand Islands. In short, the topography and islands of the Frontenac Arch act as an enormous natural dam, holding back the deep water that is Lake Ontario.

Because of its general remoteness and inaccessibility, the majority of the rocky Frontenac landscape has remained substantially intact and undeveloped. For this reason, the region’s fauna regularly traverse the arch as they travel between the two great parks. Interestingly, in the late 1990s, researchers tracked a female moose as it travelled from the heart of the Adirondacks across the Frontenac Arch, crossing the St. Lawrence River through the Thousand Islands, across TILT’s Crooked Creek Preserve, and into the remote Algonquin Provincial Park. This moose came to be known as Alice, and her story has helped bring awareness to and understanding of the existence of this Algonquin to Adirondack (A2A) wildlife corridor. Alice, among other charismatic creatures, has become the totem, justification and impetus of the Algonquin to Adirondack Collaborative.

Despite the relatively healthy and resilient condition of this region’s natural environment, there are several forces threatening the integrity of the A2A. At both the global and local scales, climate change has had detectable effects on our natural environment. In general, the Adirondacks are experiencing warmer and more erratic weather patterns. This is resulting in the northward shift of several species’ ranges that depend on the cold winters of the Adirondack Mountains. These range shifts aren’t likely to cease, as it’s estimated that the climate in the Adirondack Park will resemble that of modern day West Virginia by the end of the century. As the moose, martens, and countless others seek cooler, wetter refuge to the north, they’ll require safe passage through an intact highway: the A2A corridor.

Compounding this climatic issue is the fact that the narrowest point of the Frontenac Axis intersects with the most populous stretch of the Thousand Islands. This is an area with substantial risk of development and fragmentation, which could ultimately become a migration barrier if left unchecked. The conservation of the diverse natural habitats in the Thousand Islands region of the A2A corridor is a primary pillar of TILT’s mission, and when contemplated at the A2A scale its importance shines through.

Over the last several years, TILT has fully recognized the landscape-scale importance of the A2A migration corridor. TILT and several other regional conservation partners are diligently working to safeguard this wildlife highway for the plants and animals that live, breed, feed or migrate here. TILT is currently in the process of permanently conserving nearly 500 acres across two adjoining parcels within the bottleneck of the US Frontenac Arch. These projects build upon existing forest preserves, helping piece together a conservation bridge from the Adirondacks to the St. Lawrence for our friends of foot and feather. After all, what better way to express our gratitude and appreciation for these natural wonders than to provide them with perpetual protection!