Categories

-

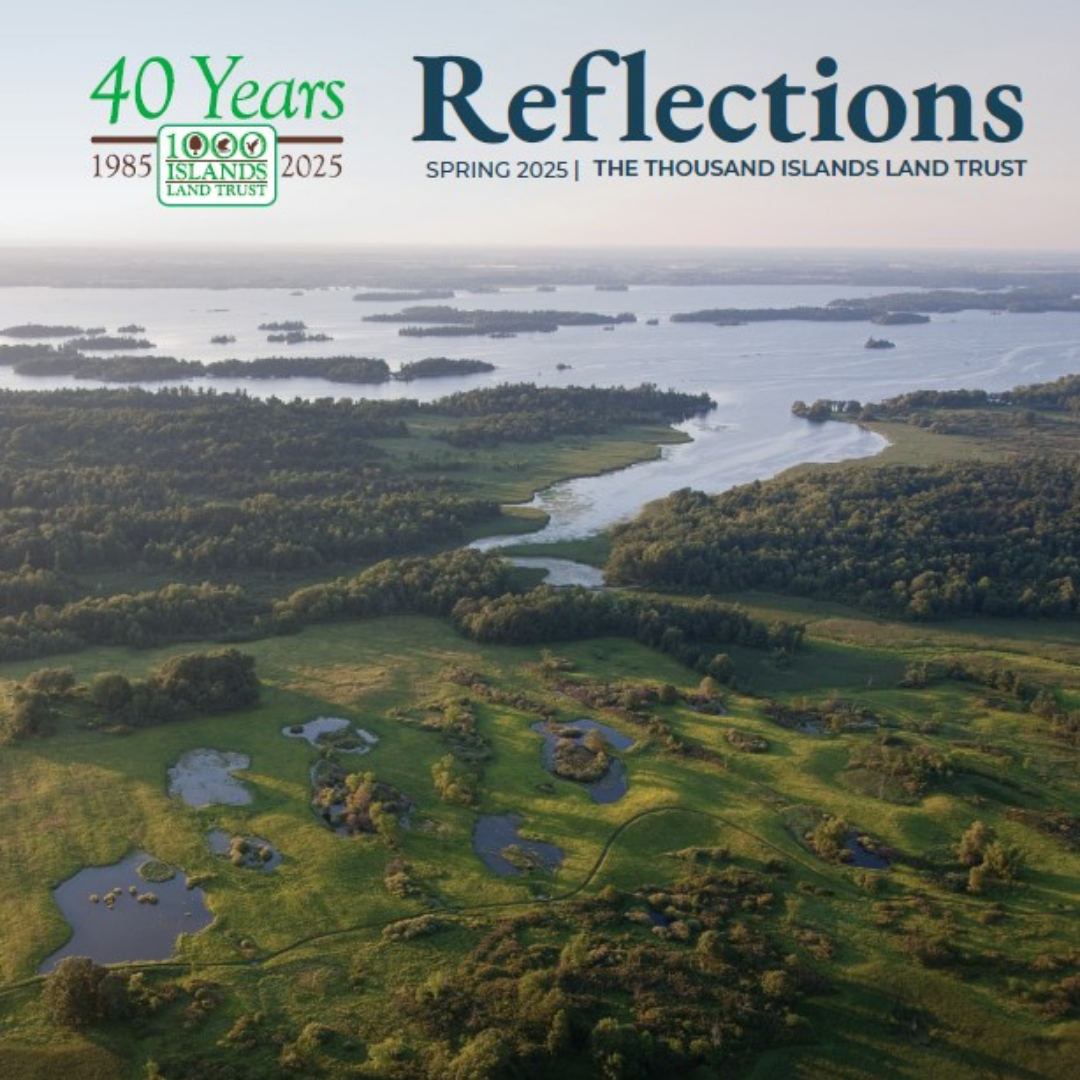

40 Years A Force

We’re excited to share that TILT was recently featured in a thoughtful and inspiring article published…

-

Look who we caught on camera! Meet the Red-tailed Hawk:

Captured in stunning detail, this pair of Red-tailed Hawks showcases the power of grace of these…

-

TILT Joins Collaborative Effort to Restore Young Forests and Protect Golden-winged Warblers

Together with the American Bird Conservancy, Ruffed Grouse Society and Indian River Lakes Conservancy, TILT is…

-

Reuniting Turcotte Farm with Zenda

For years, the Turcotte Farm stood quietly beside Zenda Farms, its fields stretching toward the horizon,…

-

Rare Habitats and Forest Connectivity in Focus

In the face of climate change, the A2A landscape is of increasing importance as species move…

-

Grindstone Island Gains 72 Acres of Protected Land

Lower Town Landing Road, the vibrant Lange Property punches above its weight in terms of conservation…

-

TILT Awarded Two Conservation Partnership Program Grants to Advance Land Protection and Community Engagement

The Thousand Islands Land Trust (TILT) announces that both proposals submitted to the New York State…

-

TILT’s Conservation Connections Program Brings Science to Life for Local Students

The Thousand Islands Land Trust (TILT) recently hosted a dynamic two-day Conservation Connections program, designed to…

-

TILT Applies for Accreditation Renewal

The Thousand Islands Land Trust (TILT), is proud to announce that they will be applying for…

-

TILT and STR Team Up for Blind Bay Shoreline Cleanup

Staff members from the Thousand Islands Land Trust (TILT) and Save The River (STR) joined forces…

-

TILT Connects Homeschool Students to Conservation at S. Gerald Ingerson Preserve

The Thousand Islands Land Trust (TILT) recently hosted a Conservation Connections field trip with a local…